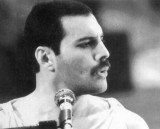

Elvis may have be the king of rock’n’roll, but God, of course, can only be Freddie!

Elvis may have be the king of rock’n’roll, but God, of course, can only be Freddie! ![]()

Even though an online poll among a meager 4000 fans (selected how? those who happened to come across the poll?) is anything but representative… a British tabloid had a brief report, Skiddle wrote a bit more about it, and Rockantenne mentioned it on the radio this morning. And I, being a Queen fan, have to write about it here, of course…

A spokesman of Onepoll (where the poll was held) said:

Everybody loved Freddie Mercury, his theatrical performances on-stage were incredible and set him apart from other rock stars.

Got nothing to add here – except for the Top 20, of course (taken from Skiddle). Queen guitarist Brian May also made this list:

- Freddie Mercury (Queen)

- Elvis Presley

- Jon Bon Jovi

- David Bowie

- Jimi Hendrix

- Ozzy Osbourne (Black Sabbath)

- Kurt Cobain (Nirvana)

- Slash (Guns N’ Roses)

- Bono (U2)

- Mick Jagger (The Rolling Stones)

- Axl Rose (Guns N’ Roses)

- Dave Grohl (Foo Fighters)

- Jim Morrison (The Doors)

- Paul McCartney (The Beatles)

- Steven Tyler (Aerosmith)

- Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin)

- Brian May (Queen)

- James Hetfield (Metallica)

- Jimmy Page (Led Zeppelin)

- Bruce Dickinson (Iron Maiden)

Since this topic briefly came up during my “mini class reunion” at Christmas, I thought I’d post it here, too, how you can calculate a weekday in your head.

Since this topic briefly came up during my “mini class reunion” at Christmas, I thought I’d post it here, too, how you can calculate a weekday in your head.